He said he was an actor. He said his brothers were actors. But they weren’t actors. They were fools. And my ex-husband Curly was the biggest fool of all.

I don’t mean to sound bitter, because people all over the world loved Curly. I did, too. Fifty years ago the man swept me off my feet. Actually, “boy” would be more precise—because that’s what he was: a child in a two hundred and sixty-three pound body. But I’ll get to that in a minute. Yes, for a brief time—fourteen months—Curly and I were happy, although looking back, I was never that happy. But I was young. A virgin, if you can believe. And to think now, that a Stooge was my first . . . my god, was I nuts?

My name is Ruth Howard Birnbaum, and it was my strange, unbelievable fate to be the second of Curly’s four wives. The other girls—Paula, Jean, and Anita—didn’t fare any better than I did. Wait, I take that back. Curly and Anita lasted four whole years. But he was out of show business then, and a lot calmer than when I met him, back in ’39. God, has it been that long?

The years have blurred our time together, but some nights, as I lie beside Irving, my husband of forty-three years, I can still feel that grubby bald head nuzzling against me, and that old maddening nyuk-nyuk-nyuk rings through my head like a curse.

I was working at Morty’s Furs on Olive Street in downtown Los Angeles. Morty was a wholesale furrier who sold coats, stoles, scarves, hats and muffs. How he survived in 80 degree weather I never figured out, but he did. Anyway, I did secretarial work: writing invoices, typing orders, and occasionally, when Morty bought a quarter-page in the L.A.; Times, I modeled a fur or two. I was nineteen, brunette, and a real looker back then.

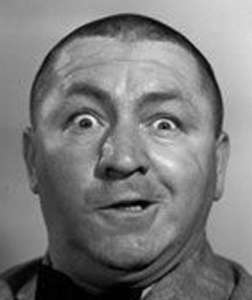

Well, it was Friday, and right before lunch, if I remember correctly. I was helping Morty wheel a rack of mothy raccoon pelts into cold storage, when I heard the front door jingle open, followed by a long, piercing wolf-whistle. I turned around, to see a bald fat man stuffed into a gray tweed suit two or three sizes too small. He wore a black bowler and a white lily boutonniere, and his slacks were hiked up around his waist in a futile effort to conceal his stomach. I watched as he lifted the bowler, did a quick drum-roll with it atop his shaved skull, and flared his eyebrows.

“Hiya, toots!” he said, in an ungodly squeak.

“Well, aren’t you fresh.”

“Fresher than a mackerel!” he said, bursting through the waist-high swinging doors.

I grabbed my purse and walked by.

“Hey, where ya goin?”

“To lunch.”

“Too bad. ‘Cause you’re one swell dame.”

“Excuse me?”

“My name’s Curly,” he said, his blue eyes sparkling. “Actually, my real name’s Jerome. Jerome Howard.” He offered his hand. “I’m an actor.” From the way he said “actor” I knew he was from New York.

“I’m late,” I said. A door-slam later I was gone.

That night, I had a date with Sherman—he was an eye, nose and throat doctor practicing in Brentwood—and Shermie drove us to one of our favorite haunts: the old Ambassador Hotel. Well, no sooner had we saddled up to the bar, ordered our gin rickeys and lit our Chesterfields, when who strolled into the lounge but you know who. He was dressed like Al Capone and the band stopped playing as he strutted through the crowd. Soon it was “Curly, let me buy you a drink,” and “You playin’ spoons tonight?” Curly laughed and hit the bar, where he was quickly surrounded.

The music started again, and all thoughts of this popular, pot-bellied stranger left me. I sat with Shermie, listening to him go on about septums, when suddenly, we heard a stir a the bar. There was conking glass, a quick mad cackle, and as Shermie turned to investigate, a jet of water blasted him in the face, sending his wire-rims across the room. At once we fell to the floor, and when we found the shattered lenses, we looked up to see who’d cause the outburst.

Standing over us, with a foot-long cigar crammed into his mouth, holding a seltzer bottle, was Curly.

“Sorry, mac,” he said, a sly grin spreading over his face.

“Why you—”

“Boys! Please!” I said, coming between them.

“Hey! You’re the dame from the fur store!”

Then with a brazenness I’d never seen in all my days, Curly asked me to dance. I was flabbergasted. How could anyone be so daring, so devil-may-care?

I don’t know what came over me, but as Sherman squinted in disbelief, I took his hand.

To my amazement, Curly was an excellent dancer, very nimble on his feet for a man of his size. We tangoed into the wee hours, see-sawing over the floor, and as Bobby Carlyle’s World Famous Players poured out the jazz, I laughed like a giddy schoolgirl. It was too much—the music, the cocktails—and I fell into Curly’s arms, captivated by the sheer oddness of his personality. As for Shermie, well, he huffed out and that was the last I saw of him.

Later than night, with the palms casting giant shadows and the lights of the city twinkling like a million fireflies, Curly drove me home in his tomato-red 1938 Buick Roadmaster convertible, and when we kissed goodnight on the stoop, I knew I was smitten. He was just so different. I’d never met a man like him. With most fellas it was “How do you do?” and “May I take your coat?” you know, real formal and all.

That’s why I fell for him. He was fun. He wasn’t the best looking guy, but did I care? After dating stuffy old Shermie, I just wanted to have a good time. And that was something Curly definitely knew how to do.

Over the next few months, we hit the town like a couple of sailors. McVickers. The Club New Yorker, Café Trocadero, we were regulars at every juke joint on the strip. Curly thought the way we met was destiny, and showered me with gifts,: jewelry, hats, patent leather shoes, even a parakeet! To my parents horror, we continued dating, and as I gazed into his eyes over a shared egg cream at one of the many soda fountains we frequented, I sensed it was all leading up to something.

Sure enough, one night at Charlie Foy’s Supper Club, Curly popped the question. If you’re imagining candlelight and violin concertos, drop the thought, because Curly proposed as only a Stooge could. Chewing greedily, with a mouthful of pork, he said:

“Warma seg me ga heech.”

“What?”

“Whaddaya say,” he grunted, finally swallowing, “we get hitched.”

I was stunned. “Okay,” I heard myself say. Curly burped, and it was done.

We were married at Temple Beth El, Curly’s parent’s synagogue on Crescent Heights. Moe was best man. Shemp was there, plus Larry Fine and Jules White, the director Curly and the boys shot with. Believe it or not, this was the first time I met any of them (Curly rarely mentioned his work—all he said was that he was an “actor.”) The ceremony was simple, and as my parents watched in dismay—I’ll never forget the look on Pop’s face—Curly slid the ring on my finger, and we were husband and wife.

That night in Reno, Curly made love to me. I don’t remember much, just squirming and chuckling in the dark, then it was over. Curly, bloated from the platters of corned beef and knish he’d packed away at the reception, didn’t have the stamina to go much longer. As he lay atop me afterwards, sticky and panting, I remember looking up at the rafters of the cabin, wondering what I’d done.

All in all, I’d dated Curly for two months, in a smoke-filled whirlwind of cocktails and late nights. Suddenly, as I listened to his peeping snores, I realized I barely knew him.

But I pushed my doubt aside. The marriage would work, I told myself.

It had to.

After the honeymoon, we moved into a seven-room home on Maple Drive in Beverly Hills. It was a grand old house, with hardwood floors, a beautiful garden, and a pool in the backyard. Quite a step up from my parent’s place in Manhattan Beach, that’s for sure!

Curly threw himself into his work, while I set about furnishing the place, picking wallpaper, hiring painters, decorators. Gradually, it became home, although I was the only one who enjoyed it, as Curly’s fall schedule busied him to the point where I only saw him n the morning, when he awoke for another sixteen hours of filming. I didn’t mind, though. I had plenty to do around the house, and with the garden, it was easy to lose myself.

Even at this point, six months into the marriage, I still hadn’t seen one of Curly’s films. I mean, he said he was a comedian, right? I figured he was like Red Skelton or Henny Youngman. It wasn’t until he started coming home with some peculiar ailments—black eyes, fat lips, whipped cream clogged in his nostrils—that I started wondering what he was doing.

One day, after Curly returned home from another long day of filming, I heard him whimpering in the bathroom. I threw open the door, to find him bent under the faucet, water spattering off his skull.

“I’m goin’ nuts! Get it out!” he yelled, his hands a blur as he slapped his face.

“What’s wrong?”

“Something’s stuck in my ear!”

I ran to the kitchen and got a pair of needle-nosed pliers.

“Hold still.”

I stuck the pliers in and fished around. It took some doing, but finally I grabbed hold of the thing and yanked. Out it came, a rock-hard plug coated in wax. I held it up to the light, but only after rinsing the gook off did I realize what it was—a cherry pit! It must have been in Curly’s ear for weeks, I mean, it was starting to blossom!

That was when I decided to see one of his “films.”

The next day I went down to Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and forked over two bits for the matinee. I knew something was wrong right as I sat down, because the only people there were drunks, servicemen, and kids playing hooky.

The picture was called “Oily to Bed, Oily to Rise,” and started normally, with Moe, Larry, and Curly driving through oil country. But when their jalopy got a flat and Curly hopped out to fix it, things took a sick turn. To my horror, Moe snatched the tire iron from Curly and conked him in the face! Over and over Moe smashed him, and I covered my eyes. The audience was in stitches, roaring like maniacs; I looked back at the screen, hoping the violence was over, but all I saw was Curly being kicked and slapped, all to excruciating sound effects. It was chaos; kids screaming, Crackerjack raining down—everyone went stark raving mad! I sat there, my jaw hung open in shock, and asd I watched Moe—his own brother—clamp a monkey wrench onto Curly’s nose and spin it around, I thought, “I’m married to that?” Reeling and in tears, I ran from the theatre, all the way down Hollywood Boulevard.

When I confronted Curly that night, he just smiled. “That’s what I do. I’m a Stooge,” he said.

“I thought you said you were an actor.”

“I am.”

“But all you did was let Moe hit you.”

“That’s actin’!”

“How do you mean?”

“Well,” he said, smirking, “I’m actin’ like Moe’s hittin’ me!”

From that day on, it was all downhill.

In a way I deserved it. But when you’re nineteen, you don’t know anything. Sometimes, love’s not meant to be—especially when you’re married to a Stooge.

My parents always said Curly was beneath me. I thought they were being snobs, but as time passed I began to see they were right. It wasn’t the double negatives he used, or his illiteracy—all he read was Li’l Abner, Nancy, and the racing forum—there was more to it than that. Once I saw those images in the theatre, our lives changed. I started to see that I wasn’t married to a man, but to an irresponsible child.

Of course, Curly didn’t help matters, because with each film, he grew increasingly unable to separate his on-screen personal from real life. That’s what wrecked our marriage—the differences, the lack of things in common, that was nothing. The big problem was that he was a Stooge twenty-four hours a day. So in a desperate attempt to save the relationship, I tried to change him. But the more I tried, the more he resisted. The Curly part of him—the only part of him I realized later—was just too strong.

All I wanted was for him to settle down, to act normal, but he was too busy being a comedian. Everything had to be a gag—eating, shopping, you name it. When he cleaned the house, he’d get tangled up in the vacuum cleaner hose, wrestling it like an anaconda. I’d give him a simple task like doing the dishes, only to find a room-full of suds and him sloshing around with soap in his eyes. None of those domestic ideas worked at all.

I don’t know how many nights we lay in bed, discussing the relationship, with him promising to change, only to have him ruin an hour of heartfelt words with one of his moronic sounds effects. And sex—you don’t even want to know about that. Let’s just say it didn’t work.

One night, we agreed to have a romantic dinner. The relationship was at an all-time low; Curly had been acting in George White’s Scandals on Broadway, and I hadn’t seen him in months. I’d gone to the market for T-bones, and it was Curly’s job to get the liquor. Well, he got it alright. And guess where it all went—every last drop of it, right down his throat.

When I came home, he was in the dining room, his shoulder pinned to the floor, running in circles, screaming whoob-whoob-whoob-whoob, like he’d gone cuckoo.

I just stood there. The room was in shambles, empty bottles and silverware on the floor, shattered china; it looked like a bomb went off. Curly kept spinning.

“Curly!”

He looked up. “N-yyAAAhh-AAAhh-ah!” he said, in that stupid nasal honk that drove me insane.

“What are you doing? “

“Mo and Larry stopped by and we—“

“Tonight was supposed to be special! Goddamn you, Curly!”

“Hey, let’s go somewhere,” he said, scrambling to his feet.

“I don’t want to go anywhere!”

“What’s wrong?”

I couldn’t believe it. Standing in the middle of the room he demolished, on the first night I’d seen him in months, he says “What’s wrong?” I dropped the steaks and stormed out.

Two weeks later, we were back together. Curly sent flowers, Candygrams, the whole shebang. He swore he’s shape up, that he’d be Jerome and not Curly. And I believed him. What else could I do?

But nothing changed. Oh, he was fine for a week or two, but as soon as Jules started filming, it was the same old Curly.

In bed he’d snore, or pass gas and laugh like a fool. He’d take baths and leave water and plastic boats all over the floor. He spent more time with his toy schnauzers Shorty and Doc than he did with me, teasing them into fits of barking that lasted for days. On weekends he’d go to the Saturday night fights and when he came home at dawn he stank of peanuts and cigars and his throat would be raw from screaming. Then, when he got up at five, he’d want breakfast. In bed.

Finally, I’d had enough. One day, after cleaning a colossal mess in the kitchen—Curly had tried to bake a poppy seed cake—I drove down to Columbia Pictures, past the security guard, right up to Lot 13, where Curly was filming “What’s The Matador?” his 62nd short.

“Where’s Curly?” I said to Jules, who sat smoking in his director’s chair.

“In wardrobe.”

I heard a tinkling of bells, and when I turned around there was Curly, wearing matador tights and a flowing red cape. A sad-looking bull trotted beside him.

“What’re you doin’ here, Ruthie?”

“I want a divorce.”

The bull separated and out of one half a sweaty-faced Moe appeared, followed by a sopping Larry at the other.

“Hey fellas! She wants a divorce!”

“Dames,” said Larry, “Hey, Moe. Got a smoke?”

“I’m serious, Curly.”

Curly started to speak, but a flurry of extras in sombreros ran by and Jules yelled into his megaphone.

“Stooges back on the set!”

Mo and Larry hopped off in the bull costume, leaving Curly and me alone in the dust.

“Curly stared at me, like he was straining to figure something out. He bit his lip. Then his face broke and he smiled.

“Why soitenly?” he snickered. “We’ll do it tomorrow!”

My heart sank, and as the sobs heaved out of me, I watched Curly skip back to the cameras, the only place, I think, he ever really wanted to be.

There aren’t many people who know all that. Oh sure, Irving knows, but he doesn’t care. He loves Curly. Saturday mornings he always wants me to watch the Stooges with him. But I can’t. I lived it.

The divorce went through, and we went our separate ways, I to a degree in pharmacology from U.C. Santa Barbara, Curly to a tour of U.S. Army camps in World War II, a round of feature films, and more shorts. Curly’s next wife, Paula, divorced him after five weeks. I must have been a masochist to stick it out a year and a half.

I’ve mellowed over the years, though. While Curly drove me crazy at the time, I realized now that he never acted like he did on purpose. He couldn’t help the way he was. I mean, with Moe and Shemp for older brothers, what chance did he have of being a normal human being? Right! None!

One day—six, seven years ago—I found a biography of him at Book Nook in the Twin Oaks Shopping Plaza. It was called Curly: A Victim of Soicumstance. And you know what? It made me cry. There was so much I never knew about him. Did you know Curly had a thick, beautiful head of hair? Jules made him shave it off because it made him look too “normal.” Ha. Thanks, Jules.

In 1946, six years after we separated, Curly had his first stroke. Shemp replaced him, and now partially paralyzed, Curly retired with his last wife Anita in Toluca Lake. He spent his last days playing with his schnauzers, and in 1952, died of a cerebral hemorrhage. I guess all those sledgehammers to the forehead took their toll.

I keep the book in an old jewelry box, up in the closet. Now and then, when I feel nostalgic, I thumb through it, and when I get to the black and white picture section in the middle, I stare into Curly’s eyes, the same eyes that Moe poked and jabbed and gouged, and I think back, to that strange, otherworldly time, when of all things to be, I was Mrs. Curly.

Then I laugh, and thank God I never had children with him.

-First published in Potpourri