This sort of amusement gives pleasure to children, silly women, slaves and free persons with the characters of slaves; but an intelligent man who weighs such matters cannot possibly approve of them.

-Marcus Tullius Cicero, E Officiis

Lactic acid boiled in the towering domes of Turbo’s pecs. Veins throbbed like angry worms and his face flushed beet-reed as he pressed one hundred twenty pounds. He held it over him, arms trembling, breath pumping rhythmically from blown-out cheeks.

Fucking pussy! Do one more! Do it! You wanna look buff for the cameras? Get psyched!

He lowered the stack, sucked air, and with an explosive, back-arching heave, raised it a glorious thirteenth time. Searing heat bored through his sternum; his arms were scalding trunks, but he couldn’t stop—thirteen was a new record! Wait until he told Torch. One more. Just. One. More.

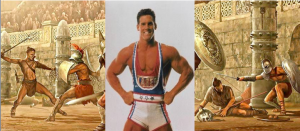

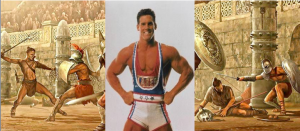

I’m a gladiator! Whirled the voice in his head. And he was—an American Gladiator. in a polyurethane and foam rubber arena he competed, using his six foot four inch, two hundred twenty-one pound Nautilus-spawned body to conquer travel agents, while a studio audience of preschoolers and adult mental defectives whooped like a rookery. It was cake—all he had to do was stay in shape, (which was easy, what with the nutritional supplements, the fat-fighting tablets of Chromium Picolinate and Inosine 500 he gobbled) fire tennis balls at leapfrogging accountants, and rake in his paycheck. Not bad for a second-string tight end two years out of USC with a degree in Health and Recreation. Not bad at all.

Steadily, he lowed the weight. One more and his pieces would be as fluffy as fresh-baked bread. Do it pussy!

But the stack refused to move. He grunted, gnashed his teeth. I’m a gladiator! I’m a gladiator! I’m a gladiator! I’m a gladiator!

Turbo heaved, muscles locked in agony, petrified, but the weight was a wall. He saw glowing patterns, orange motes, and like wisps of spiraling smoke, blackness crept in at the periphery of his vision, sweeping over the palm-printed mirror and padded machines.

He went limp and dropped into space.

With every ounce of his flagging strength Priscus lunged, parrying the thrust, the brutal clang of metal on metal reverberating in his ears. He dodged, whirling, and when the Gaul charged he hurled aside, watching him reel into the dust in a tangle of sprawling limbs and glittering steel. Gasping, he lowered his sword.

Shrack!—a hot lash stung his back. “Fight, Thracian!” cried the lanista.

His troupe of gladiators crouched beneath the broken pillars bordering the courtyard, their lances, shields and leg-greaves scattered round. Beyond them, over the low compound of stone huts, the dusky, scrub-flecked hills shimmered in the heat.

Priscus could barely raise his weapon; his arms were lead weights, thick and unmovable. Since noon he’d been battling the merciless Gaul beneath a broiling sun that heated his helmet like a kettle-pot. Dust clogged his throat. His feet flamed in his sandals. He was parched, ready to drop.

The legions had captured him near Phillipi, and after a week’s journey through the craggy, windswept mountains, they’d brought him here, to the ludus in Capua, where he’d been training with forty other expendables: Gauls, Saxons, Illyrians, slaves and war prisoners, temple robbers, the lowest of the low. Soon the caravan would start for Rome and he would fight for the emperor. There were two possibilities: the sweet palm-branch of victory, or dying alone on the blood-soaked sand.

The sun beat down. Hot breath and brute grunts peppered the air. The second stroke becomes the third!” screamed the lanista, dancing like a crab, flicking his whip, “Parry! Feint! And you—Priscus! Keep your sword up!”

Priscus smashed and swung, but with each blow the sword grew heavier. Sweat stung his eyes and he staggered blindly around. He was dizzy, roasting like meat on a spit. Sensing weakness, the Gaul closed in. Priscus saw a flash, a glint of streaking metal, but before he could react, the heavy blunt practice sword smashed into his skull.

The last thing he saw was the courtyard spilling sideways and dim yellow sky.

Turbo blinked heavily, rubbed his eyes, and the mind-wash of gray, indistinct smears spun into focus.

Pale yellow light slanted in through a barred window. Dust-specs glittered in the air. He saw chinked brick walls, an arched wooden door, a hard-packed floor littered with straw. A punishing stench—untamed by the balm of hygiene—rankled his nostrils, and from far off came the hushed roar of what sounded like a crowd.

This isn’t the weight room, he thought.

Something gray scuttled into the shadows. He lifted his head.

Three men with stony features and wild, brambly hair hunched in the corner. The middle one wore a straw-infested beard that clung to his jaw like an oriole’s nest, and jabbered in a strange tongue. He was pointing. At his feet.

Turbo gazed down, at his one hundred forty-nine dollar Nike Air Mojave II crosstrainers. Spangled in a hallucinatory web of black and white striping, the high-top, Velcro-laced sneakers looked like mounds of vanilla ice cream dripping with chocolate syrup, and glowed fluorescently in the murk.

The bearded one slid forward and lowered a gnarled finger to his sneaker-tip. Lizard-quick, he darted it back. With an awed murmur the three gathered round, poking and petting, enraptured by the shocking colors.

“Nikes,” he said. The men gaped at him, obviously confused.

This must be a joke. He was in the basement of the studio, that’s where, and these hippie freaks were part of the elaborate ruse the producers had concocted to get him stoked for the show. That was it.

Snickering at the attempt to bamboozle him, Turbo sprang to his feet, towering in the dingy space, a cornucopia of color in his bun-hugging red, white and blue Lycra unitard. He poufed his blond brush cut and unzipped his fanny pack. Whistling the first turgid notes of the Warrant classic “Cherry Pie,”—a self-motivational remnant from his football days—he dug past the vitamin pills, Q-Tips and tubes of Sportscreme, rooting for his Stiff Stuff. But before he could locate the spray can and weld his locks into place, the door exploded inward, nearly flying off its hinges as it smashed into the wall.

Two figures dressed like the U.S.C. Trojan football mascot loomed in the doorway. Turbo watched as they stormed in, grabbed the men by their ratty threadbare cloaks, and yanked them upright. The man thrashed, kicking and scuffling, but the guards, secure in their armor, had no problem hustling them out the door. Before leaving, however, the taller of the two looked back—and spotted him.

“Yo,” said Turbo, barely containing his laughter, “what’s up?”

The guard stood irresolute. Purple feathers fountained from his embossed helmet and the silver inlay on his shield sparkled. Turbo’s face folded into a knowing smirk.

“That’s some costume.”

The guard turned, yelled something he didn’t understand, and his mate reappeared. Before he knew it they’d seized him by the arm.

“Hey. Easy.”

But the rough manner in which they dragged him through the straw made Turbo realize something.

The studio didn’t have a basement.

Blaster stuck a sky-blue contact lens on his cornea and blinked it into place. Standing two sinks away, before the mirror ringed with light bulbs, Zip waved a fine-tooth comb, flicking his wet locks into a shiny black helmet. The stink of styling mousse hung heavy as they primped and posed, anointing themselves with the numberless lotions and gels scattered atop the counter.

“Getting’ psyched?” said Blaster.

“Dude, I can’t wait,” Zip said, “I’m ready to kick some butt!”

Between the lockers, Torch sat on a wooden bench, pumping his Reeboks. His auburn mane was the color of fall leaves, and draped over his leonine face. “You just gotta believe in yourself, that’s the key,” he said, more to himself than anyone else.

“It’s all positive energy,” said Zip.

“Ex-actly,” said Blaster, sliding a second lens deftly into his left eye.

Torch pulled on his elbow pads and checked his watch. “Where’s Turbo? It’s time to go.”

“Pumpin’ up,” Blaster said, “Dude won’t quit.”

“He’s gonna pop a nut.”

No sooner had Zip spoken when they heard crunching footsteps. Metal clashed, jangling like an ambulatory junkyard, and the steps grew nearer, louder, before clodhopping to a stop. Then—with a click and a whoosh, a hand-dryer clicked in. A surprised grunt sounded, and the steps started again, picking up pace, their echo lessening as they left tile and found rug.

Torch rose up from the bench and peered down the hall. Blaster and Zip crept up behind.

The dryer shut off. The only sound was the splattering showers. And footsteps.

“What is he doing?” whispered Zip.

At the far end of the locker room, a metal blade angled out from behind a pagoda of pink towels. It dipped, scraped the floor, and reemerged. From its shimmering tip, fused in a sweaty, pretzel-like knot, dangled a size 28 Bike athletic supporter.

“Turbo?” said Torch.

To Gaius Slavius Capito, trainer of the Capuan troupe, the disappearance of Priscus and his replacement by the tall blonde in the tight tunic and zebra-skin sandals was a gift from the gods, and he did not hesitate to pay tribute. Incense was lit, and a white male he-goat—symbolizing the pale stranger—was sacrificed as soon as the guards brought the captive before him. Gaius called for a soothsayer, and the seer confirmed it: the muscular warrior had been sent by the war-god Mars, to test the skill and tenacity of his fighters.

After a brief, hapless interrogation—the stranger spoke in an alien tongue and could barely utter a word without bursting into tears—the white warrior was escorted to a vestibule where he joined the other duelists to await the procession into the Colosseum. Since he’s arrived weaponless, Gaius figured him for a retarius, and had him fitted accordingly, with trident, dagger and fishing net. Strangely, the big warrior seemed bewildered when presented with these implements.

Ah, the crafty Mars! To send a fighter of such magnificence, only to have him blubber like a woman moments before battle—obviously it was a ploy, a strategy to goad his opponent into thinking the giant was weak. Gaius smiled. The cleverness of the gods—it never ceased to amaze him.

As he waited in the wings, listening to the death-squalls of the Mauretanian ostritches and wild ibex being slaughtered in the arena, he brimmed with pride. Soon the African slave-boys would rake the sand, the hacked carcasses and steaming entrails would be thrown to the dogs, and his men—all thirty of them—would battle for the emperor.

But who should oppose the white warrior? Glauco, the Syrian? Or Enomaus, the murderous Gaul?

“Who the hell’s that?” said Mike Adamle, the host of American Gladiators.

“Some clown they found in the locker rooms,” said Bruce “Ducky” Mallard, his producer. “Thinks he’s a gladiator.”

The two stood in Gladiator Arena, the huge soundstage of ramps, platforms, and padded runways where the players competed. Several yards away, a dark, rough-hewn figure wearing a sword, shield, and bronze war-helmet stood mesmerized under the blinding insanity of the strobes.

“Must’ve spent a fortune on the costume,” Mike said, glancing up from his notes. “Call security.”

Bruce shuffled uneasily in his shoes. “Mike, I’ve got, uh . . .bad news. Turbo split.”

“What to you mean he split?”

“He’s gone. We’re one gladiator short.”

Mike narrowed his eyes, gazing closer at the strange costumed figure gaping at the studio audience. Whoever the guy was, he was ripped. He looked like a statue.

“Bruce, I’ve got an idea.”

The line of stone-silent men stretched into the shadows, the crackling torches casting an orange pallor upon their grim faces. Turbo sniffled, nervously clefting his lower lip with his incisors.

In the low grotto of arched stone, workers scuttled in the dust, grappling lumber and hulks of machinery. Men in white tunics dragged canvas stretchers; a grindstone wheeled past; and with a high-pitched wincing or rope against wood, a mule-drawn cart loaded with tottering urns skirled by two feet from where he was standing. Trumpeters rag-polished horns, and back-lit by the flickering sconces, two men wearing placards and laurel garlands chatted, pointing at select men here and there. They did not point at him.

Turbo steadied his nerves. His new strategy was to lie low, regroup, figure out what was happening. He’d tried to communicate with these people; he’d begged and pleaded, blubbered and wailed, and now, his emotions spent, he settled into a quiet befuddlement. Reality or dream, wherever he was, he’d ride it out. What else could he do?

With a jingly din, two black, bare-backed men hauled in a chariot of arms: swords, daggers, scabbards, lances,; a horde of lethal points loomed like metal thistles in an ominous display. Following the chariot were the two U.S.C. Trojans who’d dragged him from the cell and the gruff thick-set man they’d brought him to—the honcho in charge.

The gruff man shouted, clapped his hands, and the group shuffled forward. Turbo gulped and fell in line. The trumpeters took their place at the head of the column, as did the men with placards. Slowly, with funereal seriousness, the line marched on, to the splash of sun gleaming at the end of the tunnel.

Just be cool, just be cool, whirled the voice in his head.

But when the procession wound out of the tunnel and the trumpeters heralded their entrance with a bugling wail and the roar of the capacity crowd rocked his ears, Turbo was overwhelmed with a spectacle more majestic, more awe-inspiring than anything he’d ever seen—even the Rose Bowl game he played a series of downs in junior year. It marveled him, took away his breath, heaved his heart into his mouth and quivered it like a toad.

A crowd of people—all wearing grayish whitish robes—sat canted back in row after row of bleachers soaring to the heavens. He gaped around. He was in a massive, bone-white bowl, a stadium. A canvas apron skirted its top level, where arched doorways hovered like cavernous eyes and red streamers flapped in the wind. Across a prairie of topaz-colored sand, a gilded box festooned in bunting jutted from the stands, where a purple-robed figure lounged in the sun, fanned by a bevy of attendants. The trumpets blasted again; the column turned, stamping through the dust, and somewhere in the dimly-lit shallows of Turbo’s mind, it dawned on him.

He was in ancient Rome!

Turbo did not arrive at this stupefying conclusion through any percipience of the classics; he knew nothing of the Punic Wars, the Pax Romana, the satires of Juvenal—no, his understanding of this period was gleaned from stereotypical sources, based on modern, overly simplified interpretations of the era. So it wasn’t until he remembered the beer-splattered toga parties at the Sigma Chi house and the movie Ben Hur, that he put it all together.

The gruff man stiffened to address the tousle-headed figure in the robe, who sipped from a chalice and watched the proceedings with a thin, superior smile.

“Ave Imperator, morituri te salutant!” came the cry.

Turbo had no idea what that meant, but he hoped it was good.

Faced with stiff competition from the ESPN networks, the ratings for American Gladiators had been sinking for two seasons, before reaching an all-time low of 1.9 in the latest Nielsens. Recently, a memo from Four Point Entertainment, the show’s production company, had been issued to the staff, and unless “new and more visually arresting contestants” could be found, the show was in danger of being canceled.

Mike Adamle knew this. Whoever the costumed stranger was, he was the answer to their prayers. Having a “real” gladiator on the show was the perfect stunt, exactly what Four Point was looking for.

However, the stranger reacted violently when the make-up girl tried to buff his cheeks, and had great difficulty understanding stage directions. No matter. A production assistant was dispatched to assist him, and the taping began as scheduled.

War-trumpets wailed in somber salvos and the crowd settled into their seats. Cries and piercing whistles cut the air as the column filed slowly back to the tunnel, followed by the chariot and its attendant slaves. The intervals between cries grew longer, until a pall fell over the arena and all was silent.

“Hey, where you . . .going?” Turbo said, nervously zipping and unzipping his fanny pack. He stutter-stepped after them, but the gruff man and the Trojans loomed at his side. Before he knew it they’d wedged a trident and fishing net into his fingers and were prodding him to the middle of the arena, where a bowl of hard-packed sand made a sort of center-ring. The gruff man patted him on the arm and walked off.

Turbo heard a creak, a long, strident moan, and turned to the opposite end of the stadium, where a braced wooden gate tottered on its hinges.

Like an insect spidering out of its lair, a tall, powerfully-built figure slid from the shadows and prowled over the sand. He wore heavy magnificent armor, with bronze leg-greaves, a large oblong shield, and a helmet with blood-red feathers. A sheathed sword wagged at his side.

An icy centipede of fear skittered down Turbo’s spine as the old rallying cry bleated insanely through his skull:

I’m a gladiator! I’m a gladiator! I’m a gladiator!

Finally, it all made sense.

Mike Adamle addressed the camera with his customary effusiveness: “Folks, have we got a treat for you! Because for the first time ever, a real live gladiator from ancient Rome will compete in Gladiator Arena! He winked slyly, pouring on the camp. “That’s right—don’t ask how he got here, but in a matter of seconds, he’ll battle Torch and Zip and the rest of our American Gladiators. Who’s tougher? The Roman? Or the Americans? Stay tuned!”

Slowly, mesmerically, Enomaus waved his sword, swiping left, right, getting a feel for it, gonging the mount against his shield. The crowd screamed barbaric slogans, writing like some massive ciliated thing, and he kept closer, gazing suspiciously at the towering figure in the tight tunic. Strangely, instead of circling in the sizing-each-other-up dance that always preceded a duel, his opponent remained stationary. The white warrior must be a superb fighter to stand so rigid and confident, he thought. He backed off.

After forging his nerves—and after being called a “eunuch” by a toothless sack-faced old hag in the front row—he charged.

“Our first event is ‘Swingshot,’ where gladiators leap from their cliffs and using the spring from bungee cords, grab red, blue, or yellow scoring markers from the center cylinder. We’re almost ready to go!”

White-flecked spittle flurried down; hisses, curses and boos stung the air as the crowd jeered, furious at the lack of blood. Turbo smiled uneasily, scuffing, back-pedaling through the dust.

“Look, I-uh, I’m not a real gladiator, like, like you are, okay? I’m an actor, on TV, and . . . this really isn’t fair.”

The man in the armor stalked closer. Wind whistled through the chinks of his armor as he fingered his sword.

“Do you think it’s fair? I mean, I don’t. So let’s—no, put that away. You win. I forfeit. Dude no, no. . . nooo!”

The underworld was nothing like Priscus had imagined. Instead of a murky realm of whispering shade and feathery spirits it was loud, alive, a pandemonium. Demons flashed swirling red eyes. Torches shed no flame and invisible dragons belched plumes of white smoke. And everywhere, stacked atop one another, the souls of the damned screamed, beating their hands in tortured agony.

The gods were angry with him. He’d died in shame, before competing in the arena, and now, like Sisyphus, he’d be tortured for all eternity. Why else had the servant of Pluto’s fastened the vine about his waist and brought him to this precipice?

He peered across the chasm, at the snake-men in banded skins atop the opposite cliff. He must conquer them—only then might the gods forgo his punishment.

A spirit with the markings of a zebra stuck a silver nut to his lips, and a trilling scream knifed the air. Priscus, flinched, arms treading wildly, and pitched over the edge.

From one end of the Colosseum to the other Turbo ran, with the clunking Gaul in hot pursuit. His one hundred nineteen dollar Nike Air Mojave II crosstrainers with the waffled outsole and snug ankle-high fit offered superior traction, allowing him to corner in the slippery dust, and the Gaul, having no such modern accouterments, lagged behind. After two orbits, Turbo spied a vague rectangle and sprinted towards it. The crowd was a seething mass, fifty-thousand voices united in a cataclysm of boiling caterwauling sound. His hamstrings felt like someone was pressing two red-hot irons against the back of his thighs and sweat stung his eyes but he made it to the door, plowing into it, bashing his fists.

“Open up! I don’t want to fight! Goddamn it open the goddamn door!”

Through the scrim of dust he saw the Gaul closing in, his sword waving like a crazy antenna.

For an agonizing second Turbo stood paralyzed, riveted to the ground, bur as the Gaul loomed over him, swinging the blade, a flash of the old magic that had earned him the title of “Mr. Football” his senior year in high school returned, and he faked right, spun, and dashed off.

“Torch and Zip are flying high, grabbing markers—and here’s the Roman with a huge leap! Looks a bit lost out there, but he’s up, and . . . look at this! He’s impaling scoring markers on his sword! Jabbing, thrusting . . . Torch has a yellow, Zip going high . . . ten seconds . . . the Roman’s got two more, three more, annnnd—there’s the buzzer! Two, three, he’s got six markers! What a performance!

Domitian scowled. This wasn’t a duel—it was a joke, two chipmunks chasing each other. He fisted the cloak of Marcus Aurelius Rufus, his prefect, yanking him near. “Find the imbecile responsible for this outrage,” he said.

“Yes, lord and god,” stammered Marcus.

Buoyed by his victory in “Swingshot,” Priscus made short work of Zip in “Tug of War,” pulling him from his elevated platform with one brutal, Herculean yank. (Zip’s gymnastic training, a plus against twentieth-century opponents, offered no advantage whatsoever against ancient brawn.) The next event, “The Wall,” a sixty-foot, toe-holed crag of vulcanized rubber, went just as smoothly, as Priscus’ tenure in the granite quarries of Thracia had bred the nimbleness of a mountain goat. He scaled the peak two and a half seconds ahead of Blaster, his nearest competitor.

After three events, Priscus led with sixteen points. Torch was second, with five, followed by Blaster with three. Zip, his shoulder purpling with a nasty bruise, was unable to compete.

Mike Adamle reminded Priscus that if he won the last event, “Assault,” he’d win twenty-five hundred dollars, and be eligible to compete in the Tournament of Champions.

Priscus was unmoved by this information.

Turbo’s heart thrashed like a hooked bass. Lungs heaving, he ran one more circuit, the stadium swirling in a kaleidoscopic blur. But right when he planted his ankle to zag across the middle, he felt a snap, a sickening rip. His foot slid, seemed to break through, and he sprawled face-first into the dust.

He spat grit from his teeth and looked down.

The white, tube-socked nubs of his toes poked out from a gaping hole of flayed rubber and ripped stitching, and the famous swoosh—sewn on by Indonesian seamstresses earning twelve cents an hour—hung by ragged threads, flapping in the sand.

His one hundred nineteen dollar Nike Air Mojave II crosstrainers had blown out from the turn!

Furry stones. Priscus patted one with his sword, amazed at how light it was. Green, too. He’d never seen such a stone.

The zebra-spirit blew the silver nut and galloped off. Priscus explored the labyrinth of Plexiglas and modular cones, and with a snapping fling, a greenish blur whistled by his helmet. There was a second fling, a third, and emerald-hued comets whizzed by inches from his leg, one passing directly between his knees, grazing his tunic. He looked up. Outlined against a nova of dazzling light, wreathed in smoke, he saw the snake-demon crouched atop a short tower, manning a catapult. Instantly, he sprang into a battle stance, shield raised, creeping stealthily on his flank, the soft stones pittering off his shield.

When he was fifty cubits away, he grabbed a stone, waited, and when a break came in the fusillade, bobbed up and threw. The stone sailed high, missed the snake-demon entirely, and hit a large spiraled gong.

A horn blew, and red lights flashed all around. Priscus sprang up to hurl a second stone, but the snake-demon was climbing down from his tower.

These demons looked fearsome, he thought, but they weren’t very fierce warriors.

They gave up too easily.

“Please—I’m just an actor, I’m not a gladiator, now I know. I’m sorry.”

But the warrior wasn’t looking at him. His head was cocked back, peering at the crowd. Turbo looked up, scanning the faces, and then he saw them.

Thumbs. One after the other, pointing to the ground.

With his victory in “Assault,” Priscus had swept all four events, attaining a record twenty-six points.

But when Mike Adamle went for a post-game interview, the stranger huffed by, shouldering into the crowd of parents and balloon-toting toddlers as they queued for the exists.

This blubbering coward had humiliated him, made him look like an ass. Enomaus swung, and in three quick, bloody strokes, it was over. The white warrior lay dead.

As they hooked the body and dragged it off in a smear of gore, he hung his head in shame.

Turbo’s unitard, fanny pack, and one hundred nineteen dollar Nike Air Mojave II crosstrainers were stripped from his body and his corpse was thrown to the hounds. The fanny packs and unitard disappeared, no doubt stolen by unscrupulous morticians, but his Nikes were saved and brought to the emperor Domitian. For several years the sneakers served as dinner party curiosities, with many a prefect of the Praetorian guard marveling at their bright colors and hexalite midsole construction. But after Domitian’s assassination in 96 A.D., they too, were lost.

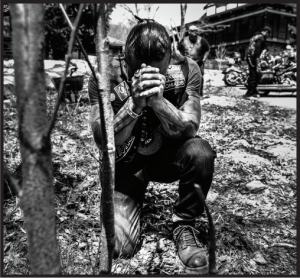

In 2002 a British expedition led by Sir Nigel Smith-Caruthers unearthed an Etruscan grave-urn on the Palatine Hill, bearing the figure of a fleeing, teary-eyed warrior clad in swoosh-emblazoned sandals. The discovery caused a minor sensation in archaeological circles, but was soon discounted as a public relations stunt once Wieden & Kennedy, Nike’s advertising agency, featured the urn in a television spot hyping its newest and most expensive crosstrainer to date, the garish one hundred and eighty-nine dollar Air Hercules.

The producers of American Gladiators launched a nation-wide search for Priscus, as the show he’d appeared on garnered the highest ratings in history. A proposal for a spin-off called “Beat The Gladiator” made the rounds among programming executives, but was scrapped as the stranger could not be found.

Three months later, Dud and Ida McGivens, a couple from Barstow, California, after reading about the “gladiator” in TV Guide, reported seeing a figure matching his description near I-15, twenty miles southwest of Las Vegas. It is now believed that the Thracian is working in some capacity at Caesar’s Palace, where to this day, his elaborate garb and ancient ways remain undetected.

Nothing is so damaging to good character than wasting time at the games; for then it is that vice steals secretly upon you through the avenue of pleasure. . . I come home more greedy, more ambitious, even more cruel and inhuman, because I have been among human beings.

-Seneca, Letters 7.3

-First published in Vignette